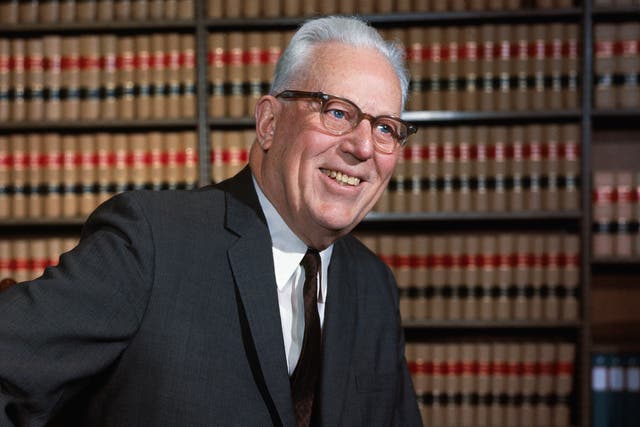

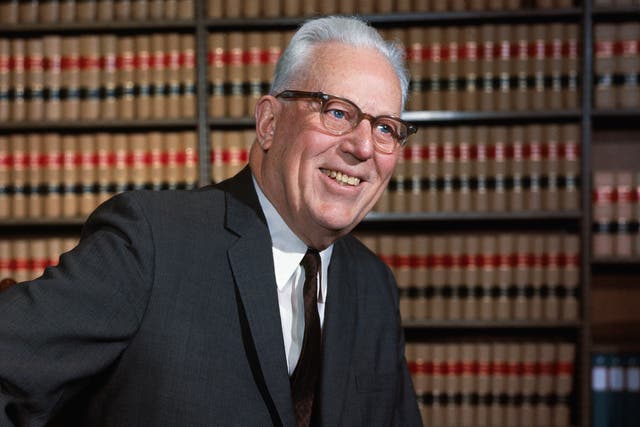

As chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, Warren led a court that decided multiple historic rulings on civil rights cases.

Published: December 5, 2022

When Earl Warren was sworn in as the 14th chief justice of the Supreme Court on October 4, 1953, the United States was on the brink of transition. The civil rights movement hadn’t officially started, but members of marginalized groups were already mobilizing for racial and economic justice.

In the 1940s, both the armed forces and Major League Baseball were desegregated, and civil rights activists began to challenge segregation in interstate travel and food establishments. The Chinese Exclusion Act, which denied Chinese laborers citizenship and immigration privileges, was repealed after taking effect in 1882. And Fred Korematsu stood up for his civil liberties, defying federal orders for Japanese Americans to move into internment camps after Japan’s 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor. As men served in the military during World War II, women entered the workforce in greater numbers and wanted more professional opportunities after it ended.

In this postwar environment, which laid the foundation for the massive social changes that would take place in the 1950s and ’60s, Warren began the first year of his 16-year tenure on the high court. Having served as California governor from 1943 to 1953 and as California Attorney General and Alameda County District Attorney prior to that, Warren replaced Chief Justice Fred Vinson, who died in September 1953.

In Warren, President Dwight D. Eisenhower saw a centrist Republican like himself with a professional background in law enforcement, to boot. Bucking conventional wisdom, however, Warren leaned left with age, perceiving the Constitution to be a living document rather than a fixed one. With this mindset, the Warren Court decided a number of landmark civil rights cases.

WATCH VIDEO: Brown v. Board of Eduction

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka that “separate but equal” schools based on race were unconstitutional. The ruling reversed the precedent established in 1896’s Plessy v. Ferguson, a case decided when Warren was just five years old. But when Brown first appeared before the court in 1952, it wasn’t clear how it would be decided. Warren’s arrival the following year changed that, according to Geoffrey R. Stone and David A. Strauss, co-authors of Democracy and Equality: The Enduring Constitutional Vision of the Warren Court . Both writers are distinguished service professors of law at the University of Chicago.

“The justices had been divided on this question the year before and had not decided the case,” Stone says of Brown. “And when Warren became Chief Justice, he worked very hard to bring everybody together, ultimately producing a unanimous decision. That was one of the great, if not the greatest decisions of the 20th century.”

Strauss attributes the unanimous decision in Brown to Warren’s political prowess. He called him one of the great politicians of his generation and a key player in the Republican Party. The GOP then, though, was not the same party it is today.

“Up until the mid-1960s, the Republican Party was pretty much united in favor of civil rights,” Strauss says. “It was a liberal wing of the Republican Party that was really adamant about pressing for civil rights, and then a more conservative wing that was not. But the hardcore segregationists were in the Democratic Party.”

The changing times also factored into the Brown ruling. Stone says that the court had a better understanding of the consequences of racial segregation than it had during Plessy v. Ferguson. There was little doubt that segregation negatively affected the academic achievement of Black Americans.

“They understood perfectly well that…racial segregation led to very different systems of education and not having the opportunity to interact with other students on both sides was a terrible consequence for the country and reaffirmed a set of values that…were incompatible with the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment,” Stone says.

Before Warren became chief justice, the Supreme Court wasn’t particularly protective of voting rights, but that changed during his tenure. In 1964’s Reynolds v. Sims, voters from Jefferson County, Alabama, objected to how the state’s legislative districts were drawn.

The Alabama constitution dictated that there be at least one elected official for every county and senatorial district. The districts, though, had been drawn with grossly uneven populations, allowing sparsely populated rural districts to dominate more populous and racially diverse urban districts. The court ruled 8-1 that the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause required legislative districts to be drawn with approximately equal numbers of constituents.

The decision derived from “the one person, one vote” principle, according to Stone and Strauss. “States can't set up their legislatures so that a minority of the voters in the state can elect the majority of the state legislature,” Strauss says. “But it was a big problem in parts of the country where there were rural areas that controlled the state government, even though a huge majority of the people lived in the cities. The Warren court put a stop to that.”

During the civil rights era, the Warren court also played an important role in the criminal justice system. Given Warren’s law enforcement background, he realized that low-income people, disproportionately people of color, were vulnerable to unfair criminal justice practices.

In 1961’s Mapp v. Ohio, the Warren Court restricted which evidence could be used in criminal prosecutions. Police had long been able to conduct unconstitutional searches—stopping a Black driver for no reason, for example, and then searching the vehicle and using any contraband found to prosecute the motorist.

“They could prosecute you for possessing drugs and didn't have to show that they had any legitimate justification for searching you,” Stone says. In Mapp, the court decided that if the police engage in an unconstitutional search, the evidence found is inadmissible in court. That decision incentivized the authorities to comply with the Fourth Amendment, which protects against unreasonable searches and seizures.

“But before the Mapp decision, they were perfectly free to engage in unconstitutional searches and use the evidence they found, and there was no real remedy because usually poor defendants have no way to sue them for damages,” Stone says. “And so the police had no reason to comply with the Fourth Amendment. So, this was another example of the court interpreting the Constitution so as to protect the rights of individuals who were engaged in the criminal justice system.”

In the 1963 case Gideon v. Wainwright, the Supreme Court made another important criminal justice decision. It ruled that states were obligated to provide counsel to defendants who could not afford to secure their own attorneys.

“That created a much better ability for individuals to be defended than simply standing there by themselves knowing no law whatsoever,” Stone says.

In 1966’s Miranda v. Arizona, the Warren Court ruled that police had to inform anyone they arrested of their right to remain silent and their right to counsel. The ruling was a response to law enforcement taking advantage of the fact that people of color, low-income people, and uneducated people who were arrested often did not know their legal rights, Stone says.

Collectively, the Warren Court’s criminal justice rulings used the Fourth, Fifth and Sixth Amendments to give more rights to socioeconomically disadvantaged people.

“Some of the criminal procedure decisions like Miranda [faced a] big outpouring of opposition,” Strauss says. “And, now, the most conservative justices are totally comfortable with Miranda. So, these cases went from being tremendously controversial to being, not only things no one wants to question, but things that, in many instances, everybody is proud of, like Brown. That's one aspect of [Warren’s] legacy.”

Before Warren’s 1969 retirement from the high court, he led the court in deciding 1967’s Loving v. Virginia. The justices ruled that legislation prohibiting interracial marriage violated the 14th Amendment’s equal protection and due process clauses. During this time, most Americans opposed interracial marriage, but the court recognized that banning these marriages amounted to racial discrimination. So, why did it take 13 years after the Brown desegregation case for the court to rule in favor of interracial marriage?

“Interracial marriage was the kind of emotional flashpoint issue that all the racists kept bringing up,” Strauss says. They said, “‘The Supreme Court wants to mongrelize the races. They want Black men marrying your white daughters.’ That was their pitch, so the Supreme Court ducked the issue for 13 years. And, then, finally in ‘67, said, ‘Okay, that's enough. We can’t forbid interracial marriages.’”

When the justices decided Brown, they knew the backlash against school desegregation would generate tremendous backlash. They didn’t want to incite more outrage by greenlighting interracial marriage. By the late 1960s, delaying the decision was no longer an option.

Nadra Nittle is a veteran journalist who is currently the education reporter for The 19th. Her writing has appeared in The Guardian, NBC News, The Atlantic, Business Insider and other outlets. She is the author of bell hooks' Spiritual Vision and other books.